Deep Mapping / VR / GIS

Deep Mapping Middletown: Designing Immersive Experiences for Spatialized Historical Data James J. Connolly John Fillwalk

Deep Mapping Middletown seeks to represent in spatial termsthe substantial archive produced by research on Muncie, Indiana, USA, the site of Robert and Helen Lynds’ seminal community studies, Middletown (1929) and Middletown in Transition (1937). The success of the Lynds’ work, which is considered to be among the most influential interpretations of twentieth-century American life, inaugurated a tradition of using this small midwestern city as a barometer for assessing broader social and cultural trends in the United States. Researchers, journalists, and filmmakers have repeatedly returned to the city over the past century to document social and cultural change, generating an extraordinarily rich multimedia archive documenting local experience. Most, though not all, of this material is accessible in digital form.

We have begun to build a multi-tiered platform that mobilizes this archive for “deep mapping” the city. By deep mapping, we mean the process of generating user-driven, multimedia depictions of a place. Drawing on postmodern theory, scholarsengaged in deep mapping have employed digital technologies to create complex representations of spaces and empower users to explore them from a variety of perspectives. Deep mapping aims to destabilize depictions of place, conveying the multiple meanings that different groups of people have assigned to specific settings and their evolution over time. Our deep mapping platform integrates GIS and immersive 3D simulationtechnology to provide access to this material and facilitate investigations of spatial-historical experience, including the evolution of racial geographies and the civic and social consequences of deindustrialization.

Part of our aim in this project is to reframe Middletown Studiesfor scholars, students, and public audiences. While there is anextraordinarily rich collection of Middletown research materials, including extensive published scholarship, hundreds of recorded interviews, thousands of photographs, hundreds of hours of films, survey results and unpublished research reports, much of the work that produced this archive rests on a problematic premise. The Lynds’ initial investigations neglected Black and other minority experiences, an oversight that many follow-up studies failed to remedy. Only since the 1970s has Middletown research has become more inclusive, incorporating the experiences of racial and ethnic minorities that the Lynds and their immediate successors ignored. Recent work has also jettisoned the anthropological gaze in favor of more collaborative approaches that share authority between researchers and community members. A key goal of Deep Mapping Middletown is to elevate this later body of work, using the multivocality inherent in deep mapping to repurpose the Middletown archive as a resource for investigating and empowering the marginalized, not just the mainstream.

In its current, prototyping stage, our project aims to overcome several technical and design challenges. These include:

1. The development and refinement of a Historical Spatial Data Infrastructure (HSDI) that include geolocated historical data from various sources and in various formats (text, image, audio, and video) ingested into a GIS, as well as tools, features, and procedures to manage and facilitate use of the data. A key part of this work is establishing lat-long coordinates for photographs and audio-visual materialas well as for passages extracted from textual sources such as oral history transcripts or ethnographic writing.

2. Application of manual and computational techniquesdeveloped by various scholars for capturing and representing vague or subjective spatial information in both 2D and 3D. The Middletown archive includes a substantial body of purposely obscured evidence in ethnographic writing, as well as spatial data contained in oral histories, and anonymized survey data. While researchers have employed a range of visualization techniques that extend beyond traditional coordinate-based cartographic methods to represent these kinds of data, we are especially interested in approaches that link vague and subjective experiential evidence to coordinate locations.

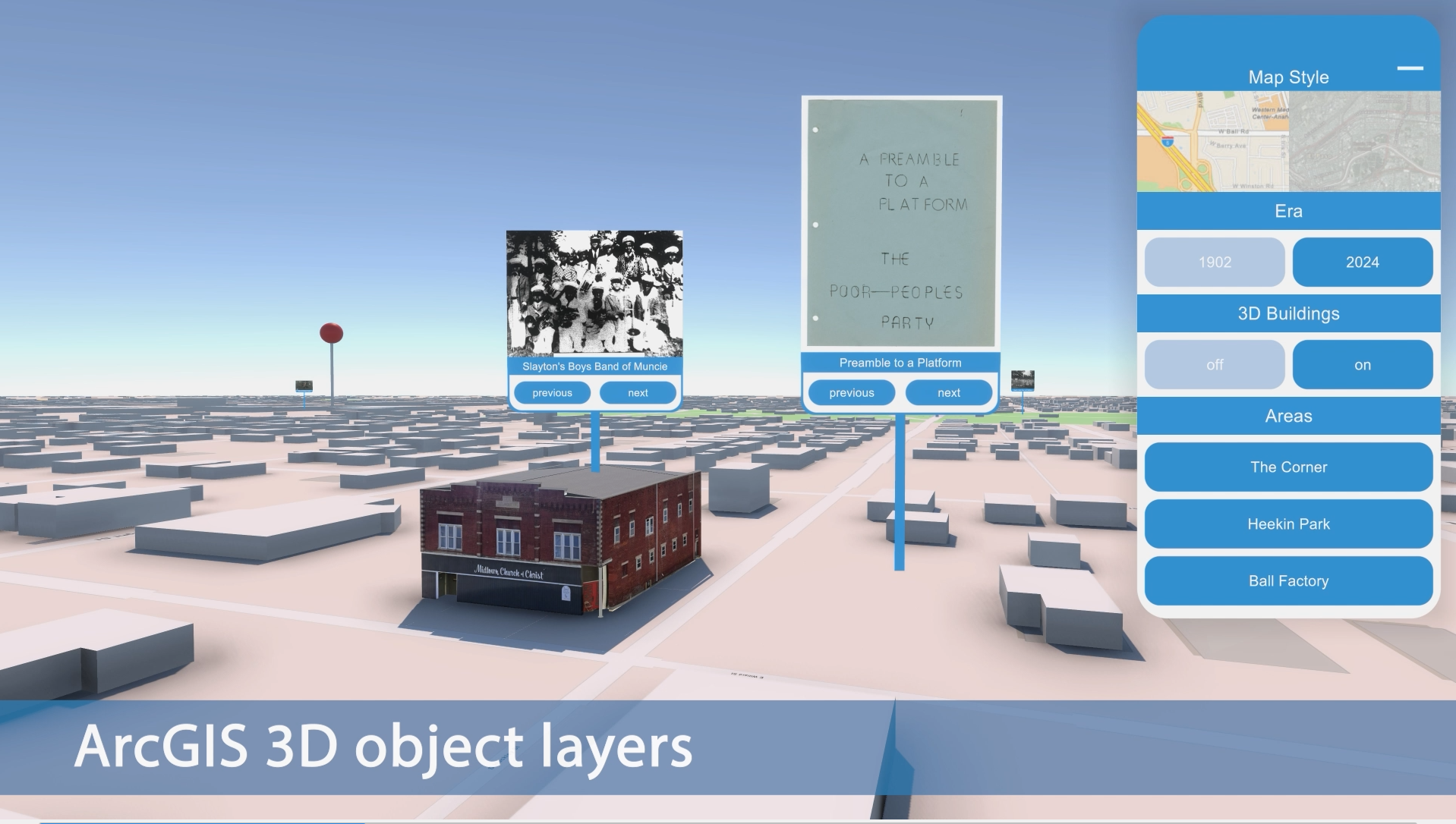

3. Development of the interface between a Unity-based virtualenvironment and a GIS-based HSDI that enables users to engage with the spatial data we are assembling.

4. Development of a virtual environment that includes in-world visual cues modeled on game analytics, such as heat maps and dwell times, that visualize spatial data, includingaffective and sensory experiences, documented in Middletown research.

We propose to present a paper documenting our progress to date in meeting these challenges and explain the potential of 3D immersion for deep mapping. Working with a team of scholarly advisors, librarians, designers and developers, we have producedan initial GIS that includes geolocated sample data for a single neighborhood drawn from collections of photographs, oral histories, and ethnographies. We have also developed a 3D immersive space using the Unity game engine, employing the ArcGIS SDK for Unity to integrate our GIS and 3D model, giving users access to spatial data within our immersive environment. We are also currently creating role-playing experiences that limit access to spaces and information depending on the role adopted by the user and the period selected. These experiences are derived from spatial data in the Middletown archive. We will also follow best practices for heritage visualization as described in the London Charter by making paradata that documents our interpretive choices available to users.

Our presentation will also include a demonstration of our prototyping work to date, including a sample walk-through of our immersive test environment and a review of the HSDI.